Dynasties, Empires, and Ages of Commerce

Development of Pacific Asia

Overview

The purpose of this chapter is to provide a general background for the major historical events and cultural patterns in the development of Pacific Asia prior to the nineteenth century. For reasons of space, much has been omitted. An additional treatment of the economic development of China, for example, may be useful in order to emphasize the technological and commercial success enjoyed by China prior to the advent of political and economic pressures from the West.

The popular misconception of the ancient, unchanging "East" should be dispelled in this overview of the region, as should the notion that Pacific Asia constituted a geographically isolated group of cultures with little interaction with the rest of the world prior to the European discoveries. Emphasis should be given to the fact that an "Age of Commerce" in Southeast Asia predated (and for a time successfully challenged) the early entry of the Portuguese.

The popular misconception of the ancient, unchanging "East" should be dispelled in this overview of the region, as should the notion that Pacific Asia constituted a geographically isolated group of cultures with little interaction with the rest of the world prior to the European discoveries. Emphasis should be given to the fact that an "Age of Commerce" in Southeast Asia predated (and for a time successfully challenged) the early entry of the Portuguese.

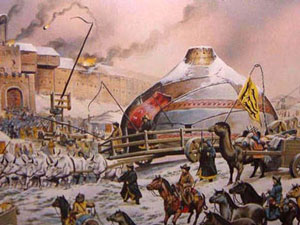

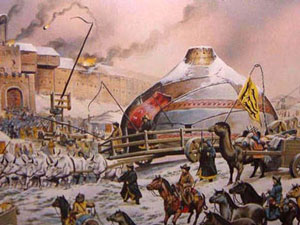

Cultural patterns that influenced the responses of different cultures to the changes in the "modern" era should also be stressed. The Introduction notes the changes and contrasts in the perspectives of cultures over the centuries. The first television segment (Module Two) points out that one of the most fundamental shifts of perspective was China's: it went from an obsession with threats from Inner Asia to a concern with maritime challenges to its sovereignty. The contrasting images here are that of the horse and rider versus those of the ship and sailor.

Overview

China

Part 1 - Introduction

Chinese history is long and complex—with records dating to around 1600 BC. Although the histories of Egypt and the Middle East are considerably older, cultural threads, exemplified in written language, architecture and other aspects of material culture, beliefs, and custom clearly link contemporary China to a distant past—more so than most contemporary cultures today. That cultural legacy has been at times a burden, but more often serves as a valued pool of philosophical, material, and spiritual traditions.

Part 2: Themes in Chinese History

Among the important themes that characterize Chinese history are the pattern of dynastic rise and fall, intermittent aggression from northern aliens, varying degrees of openness to outside cultural influences, and the dynamics of stability and social harmony. All of these themes still bear on China's stance and position in the world today. Being aware of China's history and traditional culture will enable us to better understand events presently unfolding in the country.

For in depth history please see: "Module 2: Timeline East Asian History"

http://people.cohums.ohio-state.edu/bender4/eall131/EAHReadings/module02/m02chinese.html

Overview

Japan

This section is an overview of Japanese history, from the earliest times to the present. Unlike China and Korea, the borders of Japan have stayed relatively stable throughout most of its history due to its geographic status as a group of islands. Until the mid-20th century, historic Japan was never occupied by another people and in turn never held territorial possessions on the mainland or major islands nearby until the late 19th century– though attempts were made at colonizing the Korean peninsula in the late 16th century. From the late 19th century until 1945, the imperial Japanese government had colonies in Taiwan, Korea, northeast China and, during WWII, major parts of Southeast Asia. Since 1945, Japan has remained in its traditional territory, though a few islands are still held in dispute with various states in the region.

The Japanese people of today seem to have had ancestors that came from several places. Although in antiquity the mountainous islands were once connected to the mainland, after the last Ice Age, the waters rose, isolating the island group. Whatever the origins of the earliest inhabitants were, some groups may have come from nearby Siberia, the Korean peninsula, the Yellow River and Yangzi River areas of present-day China and the southern chain of islands that lead down into Polynesia. By at least 300 BC, significant populations with advanced metal technology, rice agriculture, and horses began arriving from the Korean peninsula, and the dates of such migrations may yet be pushed back farther.

As culture developed in Japan, there were several periods when archaeological and historical evidence point to the rapid introduction of cultural elements from other places. These cultural borrowings were subsequently "re-made" in Japan to fit local needs and tastes. In some periods, cultural borrowing proceeded in a systematic matter, with definite goals in mind. This process of controlled selection and adaptation was enhanced by the island nature of the country. The Age of Reform (552-710 AD), the Meiji Period (1868-1912), and the decades right after WWII are three prominent examples. In studying modern Japanese culture, it is still possible to see "layers" of these influences from the past. At various times in history, the major sources of these influences have been states on the Korean peninsula, Silk Road cultures, China, Europe, and the United States. After periods of intense borrowing, Japan has often withdrawn into itself and the foreign cultural influences have become Japanese, sometimes taking new and creative directions. A good example would be certain styles of Japanese art and architecture that were once based on Chinese models.

It is interesting to note that in some instances the successes at borrowing and remaking were wildly successful—the modern auto industry, for example. Other experiments in cultural borrowings sometimes took unexpected directions. A good example is the attempt to introduce the Chinese-style of imperial government starting in the 7th century AD. Although certain codes and reforms were established for several centuries, the grand experiment was largely abandoned by the late 12th century, when a form of Japanese feudalism arose. In this new system, the emperor became a divine figurehead, while real power lay in the hands of the paramount military leader known as the shogun. This era gave way to a culture of warrior-aesthetes, quite distinct from the clearer separation between civil and military cultures in the Chinese state.

For in depth history please see: "Module 2: Timeline of East Asian History."

http://people.cohums.ohio-state.edu/bender4/eall131/EAHReadings/module02/m02japanese.html

Overview

Part 4 - Korea

The Korean peninsula is located at the eastern end of Asia, between China, Siberia (now part of the Russian Federation), and the islands of Japan. Because of the complex, shifting, and historic relations between these areas, as well as relations with other places such at the United Sates in more recent times, the history of Korea has been told in many ways and is still the subject of hot debate both inside and outside the Koreas. North and South Korea have different versions of the peninsula's history, both of which differ in detail and perspective from histories written in China, Japan, Russia, and the USA. The following sections, which attempt to outline the history in a balanced way, are based on a variety of materials, including lectures attended in a special workshop on Korean culture at Korea University in the summer of 1997.

The overall pattern of development in the history of the Korean peninsula is a process that begins with an unknown number of early tribal groups that populate the peninsula in prehistoric times, wandering out of Siberia and areas to the west. Over time, some of these groups form more complex societies that eventually result in early kingdoms that grow up on the peninsula; in some cases extending westwards into what is now Chinese territory. As time and events unfolded, these kingdoms were unified, though the borders and degree of unity have continued to change over time—down to today. Besides the obvious split between North and South Korea, cultural differences (including dialect, food, and local identity) exist between the various regions of the peninsula. In some cases these differences are enough to influence the results of political elections. Nevertheless, Korean culture is highly homogenous in comparison with China, and even Japan.

Over the last 2,000 years the Korean peninsula has been wracked by eight major invasions and countless smaller wars and incursions. Strategically situated on a partial land bridge in the Yellow Sea interaction sphere, the peninsula has been a natural access route for invasions to and from the Asian mainland. In times of war armies tend to push each other up and down the peninsula, guaranteeing that many areas will be subject to repeated devastation—a dynamic very prominent in the Korean War (1950-53).

Among the many invaders have been ancient Chinese kingdoms, Qidans (Khitans), Mongols, Japanese, and Manchus. In the 20th century, Korea was colonized by Japan and in the Post-WWII era was caught in the middle of conflicts between the United States, the Soviet Union, and China over the expansion of Communism in the Cold War Era – an era which still lingers in the as yet unresolved division between North and South Korea. In some cases invaders have left their mark, and even ushered in periods of positive cultural exchange, in other cases, only devastation was left in their wake. Despite these challenging circumstances, Koreans have managed to maintain a unique cultural identity that marks them as hardy survivors. Today, South Korea has among the most "wired" societies in terms of Internet access and has a dynamic economy that grew by leaps and bounds throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. South Korea has also been a leader in economic recovery after the Asian economic crisis of 1997. North Korea is poised to undergo changes within the next decades that will in part determine the stability of East Asia and the northern Pacific Rim. In short, the Korean peninsula, always integral to the dynamics of regional power and politics, will continue to play an important role on the world stage.

For in depth history please see: "Module 2: Timeline East Asian History"

http://people.cohums.ohio-state.edu/bender4/eall131/EAHReadings/module02/m02korean.html

Points for Emphasis

- It is important to emphasize distinctions between the cultures discussed in this chapter since the diversity of Pacific Asia is a central theme of the course. It may be useful to note that our characterizations of "Western" and "Eastern" culture must accommodate a wide range of ethnic traditions within each category.

- China has had a great impact on Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Each country borrowed and adapted Chinese culture and forms to suit their needs. China was also the conduit of other influences, such as Buddhism, but it is important to note that these "other influences" were themselves affected by China - signified in the process of transmission.

- Indian culture was an important influence in early Southeast Asian culture as evidenced in writing, religion, law, dance, and art. Yet the Indian forms did not fill a cultural void; they were selectively adopted by the Southeast Asians for their own purposes.

- Diverse religions have influenced different parts of Pacific Asia. Buddhism spread throughout East and Southeast Asia. Hinduism spread into Southeast Asia, and, although it was largely supplanted by Islam, it left a strong imprint on Southeast Asia. Islam spread through maritime Southeast Asia and is a powerful factor in modern politics. Christianity has had the most impact in the Philippines and Korea.

- The historical and contemporary geographical characteristics of East and Southeast Asia, and their interactions, including identification of all countries, major cities, landforms, rivers, as well as political and economic linkages are vital to the development of the Pacific Basin.

Review Questions

- After reading Chapter 1, it should be clear that the countries and cultures of the Asia-Pacific region have as many differences as similarities. How does a culture maintain its distinctness in the face of persistent cultural and political influences from the outside?

- Considering the enormity of Chinese impact on the region, why did China not conquer it all? Contrast the Chinese Empires with the Roman Empire.

- In what ways did Indian culture affect East Asia? How was this different from India's impact on Southeast Asia?

- Throughout its history, Japan has borrowed from China, yet Japanese culture is as disparate from Chinese tradition as Italian culture is from Greek tradition. Why?

- Compare and contrast Angkor and Srivijaya. What were each state's strengths and weaknesses? What contributed to the fall of each state?

Biographies

Kublai Khan - Part 1

Grandson of Genghis Khan Kublai Khan lived from 1215 to 1294. He was the grandson of Genghis Khan. Kublai conquered China and became the first emperor of the Yuan or Mongol dynasty. In theory, he was the ruler of all of the lands conquered by the Mongols. In practice, he was the emperor of China and he paid relatively little attention to his other territories. In lived from 1215 to 1294. He was the only Khan who looked upon power in a "traditional" way. Most of the Khans viewed power as a personal or family affair. Kublai Khan viewed power as an attempt to rule and govern a state, and to provide for the continuing of his regime.

Kublai Khan was the fourth son of Tolui, the youngest of Genghis' four sons by his favorite wife. Kublai' Khan began to play a role in Mongol politics when-he was in his mid-thirties (1251). His brother, Mongke, who was the Great Khan, decided to conquer Sung China. Kublai Khan was given responsibility for the civil and military affairs of China. Although he could never read or write Chinese, he surrounded himself with talented Confucian advisors. He saw the relationship and interdependence of ruler and ruled.

Kublai Khan - Part 2

In April of 1260, at a Kuritali, or great assembly, Kublai was unanimously elected the Great Khan. His brother, Arigboge, at the same time, held a Kuritali, and declared himself Khan. There seemed to be some question about Kublai Khan's legitimacy. In 1264, Kublai Khan defeated his brother, who died two years later. The family feud continued until the end of Kublai's life. The members of the family who were against him, resented the abandonment of the old ways of the steppe. Kaidu, who was grandson of Ogodei, held control of Mongolia and Turkistan until his death in 1301. The continuing warfare between 1250 and 1350, showed how deeply Kublai had identified himself with the Chinese world. Genghis Khan had been strong and ruthless enough to make the clans and families obey his will. Kublai, although powerful, was not strong enough to control Genghis' other grandsons across the vast Mongol empire. In 1267, Kublai Khan again attacked Sung China in the south. By 1279, all of China was controlled by Kublai Khan. He attempted, without much success to invade Indochina, Java, and Japan. Mongol armies suffered some disastrous defeats in these campaigns. The Vietnamese were able to resist him. Mongol cavalry did not do well in the jungles of Vietnam. (Americans, please take note).

In 1274, and again in 1281, invasion fleets, sent to Japan were destroyed by bad policy and the Divine Wind (Kamikaze). But Kublai focused most of his attention on China. The Khan divided the population of China into four groups: At the top were the Mongols, who formed a privileged military caste of several hundred thousand people. They were exempt from taxation and lived on great estates which were "staffed" by Chinese peasants. The second group were the various people of central Asia (speakers of Turkic languages), allies of the Mongols, who were also given positions of importance and tax exempt status. The third class was made up of the Han-jen or northern Chinese. The fourth group was the Man-tzu, who lived in what had been Sung China. These last two classes were greatly exploited by the rulers. For the most part Kublai Khan was not a cruel person, and could even be humane and magnanimous. Perhaps this was because Kublai Khan was very interested in religion. His reign was a time of toleration for the rival religions, and Kublai seemed to be most favorably impressed by Buddhism. Kublai also looked with favor on Confucianism, Taoism, and Islam. He was somewhat curious about Christianity, but felt he could not believe in it.

In 1274, and again in 1281, invasion fleets, sent to Japan were destroyed by bad policy and the Divine Wind (Kamikaze). But Kublai focused most of his attention on China. The Khan divided the population of China into four groups: At the top were the Mongols, who formed a privileged military caste of several hundred thousand people. They were exempt from taxation and lived on great estates which were "staffed" by Chinese peasants. The second group were the various people of central Asia (speakers of Turkic languages), allies of the Mongols, who were also given positions of importance and tax exempt status. The third class was made up of the Han-jen or northern Chinese. The fourth group was the Man-tzu, who lived in what had been Sung China. These last two classes were greatly exploited by the rulers. For the most part Kublai Khan was not a cruel person, and could even be humane and magnanimous. Perhaps this was because Kublai Khan was very interested in religion. His reign was a time of toleration for the rival religions, and Kublai seemed to be most favorably impressed by Buddhism. Kublai also looked with favor on Confucianism, Taoism, and Islam. He was somewhat curious about Christianity, but felt he could not believe in it.

Under his rule the common people of China became progressively poorer. The Mongol and Turkic officials spent more time robbing China than ruling it. The Chinese system for appointing officials, the Confucian examination system, was no longer used. This system of corrupt officials would lead, in the next century, to the economic uprisings that would destroy the dynasty. His personality is difficult to describe because we only have Marco Polo's account of Kublai Khan. Polo treats Kublai Khan as the ideal of a universal sovereign. He also, however, had weaknesses: Overindulgence in feasting and hunting, a complicated and expensive sex life, a lack of proper supervision over his subordinates, and several outbursts of cruelty. Some would say that Kublai failed in his dual role as Great Khan and emperor of China. In a sense, he fought the Mongols (that is to say other members of his family and the other Khanates). He allowed control of affairs in the vast steppes to slip from his control. He spent most of his time and effort on China.

Biographies

Buddha - Part 1

He was the chief son of a tribal group, the Shakyas, so he was born a Kshatriya around 566 BC. At the age of twenty-nine, he left his family in order to lead an ascetic life. A few years later he reappears with a number of followers; he and his followers devote their lives to "The Middle Way," a lifestyle that is midway between a completely ascetic lifestyle and one that is world-devoted. At some point he gained enlightenment" and began to preach this new philosophy in the region of Bihar and Uttar Kadesh. His teaching lasted for several decades and he perished at a very old age, somewhere in his eighties. Following his death, only a small group of followers continued in his footsteps. Calling themselves bhikkus , or "disciples," they wandered the countryside in yellow robes (in order to indicate their bhakt , or "devotion" to the master). For almost two hundred years, these followers of Buddha were a small, relatively inconsequential group among an infinite variety of Hindu sects. But when the great Mauryan emperor, Asoka, converted to Buddhism in the third century BC, the young, inconsequential religion spread like wildfire throughout India and beyond. Most significantly, the religion was carried across the Indian Ocean (a short distance, actually) to Sri Lanka. The Buddhists of Sri Lanka maintained the original form of Siddhartha's teachings, or at least, they maintained a form that was most similar to the original. While in the rest of India, and later the world, Buddhism fragmented into a million sects, the original form, called Theravada Buddhism, held its ground in Sri Lanka.

He was the chief son of a tribal group, the Shakyas, so he was born a Kshatriya around 566 BC. At the age of twenty-nine, he left his family in order to lead an ascetic life. A few years later he reappears with a number of followers; he and his followers devote their lives to "The Middle Way," a lifestyle that is midway between a completely ascetic lifestyle and one that is world-devoted. At some point he gained enlightenment" and began to preach this new philosophy in the region of Bihar and Uttar Kadesh. His teaching lasted for several decades and he perished at a very old age, somewhere in his eighties. Following his death, only a small group of followers continued in his footsteps. Calling themselves bhikkus , or "disciples," they wandered the countryside in yellow robes (in order to indicate their bhakt , or "devotion" to the master). For almost two hundred years, these followers of Buddha were a small, relatively inconsequential group among an infinite variety of Hindu sects. But when the great Mauryan emperor, Asoka, converted to Buddhism in the third century BC, the young, inconsequential religion spread like wildfire throughout India and beyond. Most significantly, the religion was carried across the Indian Ocean (a short distance, actually) to Sri Lanka. The Buddhists of Sri Lanka maintained the original form of Siddhartha's teachings, or at least, they maintained a form that was most similar to the original. While in the rest of India, and later the world, Buddhism fragmented into a million sects, the original form, called Theravada Buddhism, held its ground in Sri Lanka.

Buddha - Part 2

That's all we know about the historical life of Siddhartha, his mission, and the fate of his teachings. When we move into the Buddhist histories the record becomes much more uncertain particularly since the events of the Buddha's life vary from sect to sect. What follows, however, is the most common outline of the nature of Siddhartha's life and philosophy. When Siddhartha Gautama was born, a seer predicted that he would either become a great king or he would save humanity. Fearing that his son would not follow in his footsteps, his father raised Siddhartha in a wealthy and pleasure-filled palace in order to shield his son from any experience of human misery or suffering. This, however, was a futile project, and when Siddhartha saw four sights: a sick man, a poor man a beggar and a corpse he was filled with infinite sorrow for the suffering that humanity has to undergo. After seeing these four things, Siddhartha then dedicated himself to finding a way to end human suffering. He abandoned his former way of life, including his wife and family, and dedicated himself a life of extreme asceticism. So harsh was this way of life that he grew thin enough that he could feel hands if he placed one on the small of his back and the other on his stomach. In this state of wretched concentration, in heroic but futile self-denial, he overheard a teacher speaking of music. If the strings the instrument are set too tight, then the instrument will not play harmoniously. If the strings are set too loose, the instrument will not produce music. Only the middle way, not too tight and not too loose, produce harmonious music. This chance conversation changed his life overnight. The goal was not to live a completely worldly life, nor was it to live a life in complete denial of the physical body, but to live in a Middle Way. The way out of suffering was through concentration, and since the mind was connected to the body, denying the body would hamper concentration, just as overindulgence would distract one from concentration. With this insight, Siddhartha began a program of intense yogic meditation beneath a pipal tree in Benares. At the end of this program, in a single night, Siddhartha came to understand all his previous lives and the entirety of the cycle of birth and rebirth, or samsara, and most importantly, figured out how to end the cycle of infinite sorrow. At this point, Siddhartha became the Buddha, or "Awakened One." Instead, however, of passing out of this cycle himself, he returned to the world of humanity in order to teach his new insights and help free humanity of their suffering.

Buddha - Part 3

His first teaching took place at the Deer Park in Benares. It was there that he expounded his "Four Nobel Truths," which are the foundation of all Buddhist belief:

- All human life is suffering (dhukka ).

- All suffering is caused by human desire, particularly the desire that impermanent things be permanent.

- Human suffering can be ended by ending human desire.

- Desire can be ended through eight ways, the "Eightfold Noble Path": right understanding, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood right effort right mindfulness and right concentration.

From a metaphysical standpoint, these Noble Truths make up and derive from a single fundamental Truth (in Sanskrit, Dharma, and in Pali, Dhamma). The Buddhist Dharma is based on the idea that everything in the universe is causally linked. All things are composite things, that is, they are compose of several elements. Because all things are composite, they are all transitory, for the elements come together and then fall apart. It is this transience that causes human beings to sorrow and to suffer. We live in a body, which is a composite thing, but that body decays, sickens, and eventually dies though wish it to do otherwise. Since everything is transient, that means that there can be no eternal soul either in the self or in the universe. This, then, is the eternal truth of the world: everything is transitory, sorrowful, and soulless - three-fold character of the world.

The popular misconception of the ancient, unchanging "East" should be dispelled in this overview of the region, as should the notion that Pacific Asia constituted a geographically isolated group of cultures with little interaction with the rest of the world prior to the European discoveries. Emphasis should be given to the fact that an "Age of Commerce" in Southeast Asia predated (and for a time successfully challenged) the early entry of the Portuguese.

The popular misconception of the ancient, unchanging "East" should be dispelled in this overview of the region, as should the notion that Pacific Asia constituted a geographically isolated group of cultures with little interaction with the rest of the world prior to the European discoveries. Emphasis should be given to the fact that an "Age of Commerce" in Southeast Asia predated (and for a time successfully challenged) the early entry of the Portuguese.

In 1274, and again in 1281, invasion fleets, sent to Japan were destroyed by bad policy and the Divine Wind (Kamikaze). But Kublai focused most of his attention on China. The Khan divided the population of China into four groups: At the top were the Mongols, who formed a privileged military caste of several hundred thousand people. They were exempt from taxation and lived on great estates which were "staffed" by Chinese peasants. The second group were the various people of central Asia (speakers of Turkic languages), allies of the Mongols, who were also given positions of importance and tax exempt status. The third class was made up of the Han-jen or northern Chinese. The fourth group was the Man-tzu, who lived in what had been Sung China. These last two classes were greatly exploited by the rulers. For the most part Kublai Khan was not a cruel person, and could even be humane and magnanimous. Perhaps this was because Kublai Khan was very interested in religion. His reign was a time of toleration for the rival religions, and Kublai seemed to be most favorably impressed by Buddhism. Kublai also looked with favor on Confucianism, Taoism, and Islam. He was somewhat curious about Christianity, but felt he could not believe in it.

In 1274, and again in 1281, invasion fleets, sent to Japan were destroyed by bad policy and the Divine Wind (Kamikaze). But Kublai focused most of his attention on China. The Khan divided the population of China into four groups: At the top were the Mongols, who formed a privileged military caste of several hundred thousand people. They were exempt from taxation and lived on great estates which were "staffed" by Chinese peasants. The second group were the various people of central Asia (speakers of Turkic languages), allies of the Mongols, who were also given positions of importance and tax exempt status. The third class was made up of the Han-jen or northern Chinese. The fourth group was the Man-tzu, who lived in what had been Sung China. These last two classes were greatly exploited by the rulers. For the most part Kublai Khan was not a cruel person, and could even be humane and magnanimous. Perhaps this was because Kublai Khan was very interested in religion. His reign was a time of toleration for the rival religions, and Kublai seemed to be most favorably impressed by Buddhism. Kublai also looked with favor on Confucianism, Taoism, and Islam. He was somewhat curious about Christianity, but felt he could not believe in it.  He was the chief son of a tribal group, the Shakyas, so he was born a Kshatriya around 566 BC. At the age of twenty-nine, he left his family in order to lead an ascetic life. A few years later he reappears with a number of followers; he and his followers devote their lives to "The Middle Way," a lifestyle that is midway between a completely ascetic lifestyle and one that is world-devoted. At some point he gained enlightenment" and began to preach this new philosophy in the region of Bihar and Uttar Kadesh. His teaching lasted for several decades and he perished at a very old age, somewhere in his eighties. Following his death, only a small group of followers continued in his footsteps. Calling themselves bhikkus , or "disciples," they wandered the countryside in yellow robes (in order to indicate their bhakt , or "devotion" to the master). For almost two hundred years, these followers of Buddha were a small, relatively inconsequential group among an infinite variety of Hindu sects. But when the great Mauryan emperor, Asoka, converted to Buddhism in the third century BC, the young, inconsequential religion spread like wildfire throughout India and beyond. Most significantly, the religion was carried across the Indian Ocean (a short distance, actually) to Sri Lanka. The Buddhists of Sri Lanka maintained the original form of Siddhartha's teachings, or at least, they maintained a form that was most similar to the original. While in the rest of India, and later the world, Buddhism fragmented into a million sects, the original form, called Theravada Buddhism, held its ground in Sri Lanka.

He was the chief son of a tribal group, the Shakyas, so he was born a Kshatriya around 566 BC. At the age of twenty-nine, he left his family in order to lead an ascetic life. A few years later he reappears with a number of followers; he and his followers devote their lives to "The Middle Way," a lifestyle that is midway between a completely ascetic lifestyle and one that is world-devoted. At some point he gained enlightenment" and began to preach this new philosophy in the region of Bihar and Uttar Kadesh. His teaching lasted for several decades and he perished at a very old age, somewhere in his eighties. Following his death, only a small group of followers continued in his footsteps. Calling themselves bhikkus , or "disciples," they wandered the countryside in yellow robes (in order to indicate their bhakt , or "devotion" to the master). For almost two hundred years, these followers of Buddha were a small, relatively inconsequential group among an infinite variety of Hindu sects. But when the great Mauryan emperor, Asoka, converted to Buddhism in the third century BC, the young, inconsequential religion spread like wildfire throughout India and beyond. Most significantly, the religion was carried across the Indian Ocean (a short distance, actually) to Sri Lanka. The Buddhists of Sri Lanka maintained the original form of Siddhartha's teachings, or at least, they maintained a form that was most similar to the original. While in the rest of India, and later the world, Buddhism fragmented into a million sects, the original form, called Theravada Buddhism, held its ground in Sri Lanka.