Kublai Khan - Part 2

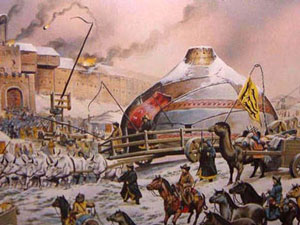

In April of 1260, at a Kuritali, or great assembly, Kublai was unanimously elected the Great Khan. His brother, Arigboge, at the same time, held a Kuritali, and declared himself Khan. There seemed to be some question about Kublai Khan's legitimacy. In 1264, Kublai Khan defeated his brother, who died two years later. The family feud continued until the end of Kublai's life. The members of the family who were against him, resented the abandonment of the old ways of the steppe. Kaidu, who was grandson of Ogodei, held control of Mongolia and Turkistan until his death in 1301. The continuing warfare between 1250 and 1350, showed how deeply Kublai had identified himself with the Chinese world. Genghis Khan had been strong and ruthless enough to make the clans and families obey his will. Kublai, although powerful, was not strong enough to control Genghis' other grandsons across the vast Mongol empire. In 1267, Kublai Khan again attacked Sung China in the south. By 1279, all of China was controlled by Kublai Khan. He attempted, without much success to invade Indochina, Java, and Japan. Mongol armies suffered some disastrous defeats in these campaigns. The Vietnamese were able to resist him. Mongol cavalry did not do well in the jungles of Vietnam. (Americans, please take note).

In 1274, and again in 1281, invasion fleets, sent to Japan were destroyed by bad policy and the Divine Wind (Kamikaze). But Kublai focused most of his attention on China. The Khan divided the population of China into four groups: At the top were the Mongols, who formed a privileged military caste of several hundred thousand people. They were exempt from taxation and lived on great estates which were "staffed" by Chinese peasants. The second group were the various people of central Asia (speakers of Turkic languages), allies of the Mongols, who were also given positions of importance and tax exempt status. The third class was made up of the Han-jen or northern Chinese. The fourth group was the Man-tzu, who lived in what had been Sung China. These last two classes were greatly exploited by the rulers. For the most part Kublai Khan was not a cruel person, and could even be humane and magnanimous. Perhaps this was because Kublai Khan was very interested in religion. His reign was a time of toleration for the rival religions, and Kublai seemed to be most favorably impressed by Buddhism. Kublai also looked with favor on Confucianism, Taoism, and Islam. He was somewhat curious about Christianity, but felt he could not believe in it.

In 1274, and again in 1281, invasion fleets, sent to Japan were destroyed by bad policy and the Divine Wind (Kamikaze). But Kublai focused most of his attention on China. The Khan divided the population of China into four groups: At the top were the Mongols, who formed a privileged military caste of several hundred thousand people. They were exempt from taxation and lived on great estates which were "staffed" by Chinese peasants. The second group were the various people of central Asia (speakers of Turkic languages), allies of the Mongols, who were also given positions of importance and tax exempt status. The third class was made up of the Han-jen or northern Chinese. The fourth group was the Man-tzu, who lived in what had been Sung China. These last two classes were greatly exploited by the rulers. For the most part Kublai Khan was not a cruel person, and could even be humane and magnanimous. Perhaps this was because Kublai Khan was very interested in religion. His reign was a time of toleration for the rival religions, and Kublai seemed to be most favorably impressed by Buddhism. Kublai also looked with favor on Confucianism, Taoism, and Islam. He was somewhat curious about Christianity, but felt he could not believe in it.

Under his rule the common people of China became progressively poorer. The Mongol and Turkic officials spent more time robbing China than ruling it. The Chinese system for appointing officials, the Confucian examination system, was no longer used. This system of corrupt officials would lead, in the next century, to the economic uprisings that would destroy the dynasty. His personality is difficult to describe because we only have Marco Polo's account of Kublai Khan. Polo treats Kublai Khan as the ideal of a universal sovereign. He also, however, had weaknesses: Overindulgence in feasting and hunting, a complicated and expensive sex life, a lack of proper supervision over his subordinates, and several outbursts of cruelty. Some would say that Kublai failed in his dual role as Great Khan and emperor of China. In a sense, he fought the Mongols (that is to say other members of his family and the other Khanates). He allowed control of affairs in the vast steppes to slip from his control. He spent most of his time and effort on China.